Marcel Breuer and the Art of Space: A New Podcast Tour of an Architectural Icon<br>

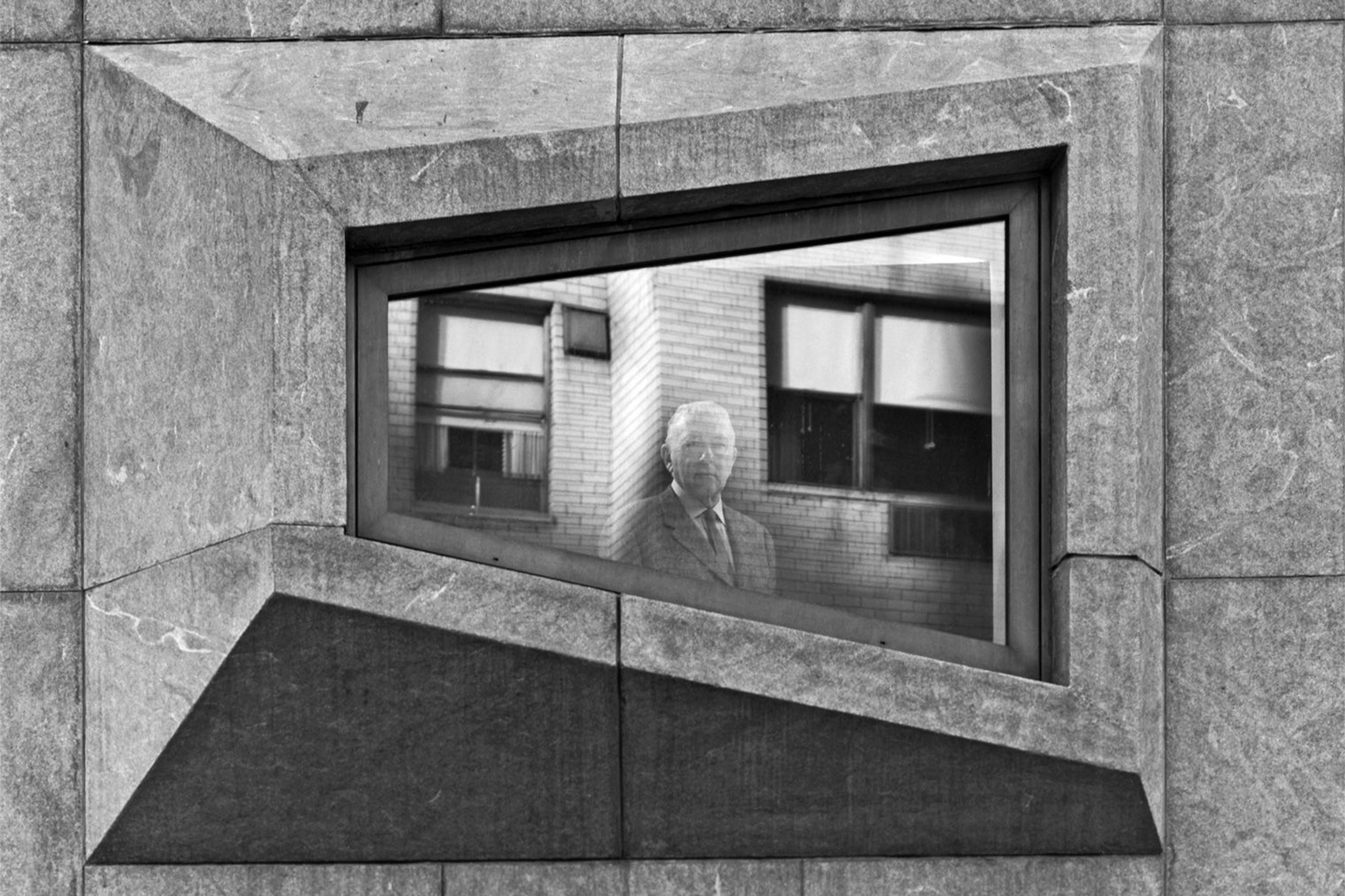

Ezra Stoller (American, 1915–2004). Marcel Breuer at The Whitney Museum of American Art, now The Met Breuer (detail), 1967. Image © Ezra Stoller / Esto

It'd be tough to pass by 75th Street and Madison Avenue in New York City without noticing the strong and imposing building on the southeast corner. It has no interest in "blending in." Instead, the enormous, angular structure, surrounded by stately Upper East Side townhomes, commands the attention of native New Yorkers and first-time visitors alike. Who designed it and why? And how did it end up here?

Answers to these questions and plenty more can be heard in a newly released podcast-style Audio Guide, available in the Museum and online. The Met Breuer Architecture Tour offers a series of lively, behind-the-scenes vignettes about this iconic building, its remarkable history, and its architect. The entire tour is half an hour long and made up of seven chapters. Its hosts are insiders who share their unique insights on the architect, his creation, and the decades-long debate on the meaning and legacy of this iconic building.

The Met Breuer is located in the Upper East Side neighborhood of Manhattan, at 945 Madison Avenue. "A museum in Manhattan," Breuer said, ". . . should transform the vitality of the street into the sincerity and profundity of art."

Truth be told, the architect, Marcel Breuer, began this building with a question of his own. In 1963 the Whitney Museum of American Art was searching for an architect to design a new uptown location that would showcase their growing collection. Competition for the commission was stiff. Several years earlier, Frank Lloyd Wright radically redefined what an art museum could look like when he created the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, a "temple of the spirit," in 1959. Now Breuer believed it was his turn. "What should a museum look like, a museum in Manhattan?" was Breuer's opening gambit to the board. His answer, he announced, was a new kind of museum that should "transform the vitality of the street into the sincerity and profundity of art."

Breuer won the bid for a building conceived as "sculptural form," to use the words of Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art. Author and historian Barry Bergdoll describes the Museum as a work of art that would house other works of art. And for nearly half a century, Breuer's building did indeed house the Whitney's collection and exhibitions. When that institution moved downtown, in 2014, to a larger space designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Renzo Piano, The Met took over the lease at 945 Madison Avenue and renamed the building after its architect. Following an ambitious restoration, The Met Breuer opened on March 18, 2016. An inaugural exhibition on Nasreen Mohamedi placed the modern artist in a modernist setting, while Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, a survey of incomplete works of art from the Renaissance to the present day, supported, The Met said at the time, "an integrated experience of art and architecture."

During restoration the 375 lights in the lobby were replaced with energy-efficient LED bulbs.

The stairwell's banisters are made of teak and capped with blackened brass.

Yet until now, visitors curious about Marcel Breuer and his museum-as-work-of-art have had no immediate way, other than turning to published materials or asking Museum staff, to get their questions about the artistry and history of the building answered. Enter my team in the Digital Department and our new podcast-style Audio Guide, which explores the building from its controversial early days through its recent restoration, as well as its lasting legacy. The material is designed to accompany listeners as they walk through the building at their own pace. As they're guided to appreciate specific physical details around them, their actual experience is grounded in larger, sometimes philosophical stories: How might we better appreciate this architect? Where does his work sit in the broader historical context of the Bauhaus and the Brutalist movement that grew out of it?

Our project began simply enough. We approached The Met's Visitor Experience staff—the experts who greet and converse with the public every day—and asked them to share the public's top questions. Who was Marcel Breuer? How many lights are there in the lobby? What does "Brutalist" actually mean? And hey, is this building even an example of Brutalist architecture? (Spoiler alert: not necessarily.) Oh, um, how do you pronounce Breuer's name? My team took those questions straight from the public and then created a tour to answer them.

Breuer took inspiration from ancient ziggurats in designing the exterior of the Museum, which sits on a plot of land that's only 104 by 125 feet. "Today's structure, in its most expressive form, is hollow below and substantial on top, just the reverse of the pyramid," Breuer said. "It represents a new epoch in the history of man, the realization of one of his oldest ambitions: the defeat of gravity."

We had to buckle up for some disagreements. Though opinions about the building have oscillated wildly since 1966, when the "Madison Avenue Monster" opened, today most agree that the building has weathered the initial rounds of outrage and ridicule to emerge as an international icon. That path, however, maps a compelling story. While aficionados appreciate the building's powerful design, others sometimes find the architecture bewildering, intimidating, or even ugly. The Met Breuer Architecture Tour dives into these debates and conversations—and comes out the other side with some answers.

While we're on the topic, I'll admit the voice of the tour is shaped by one of my own pet peeves. In so much writing about architecture, authors and critics seem to delight in alienating legitimately curious readers with writing that's overly technical, rarified—or even both. But why? Architecture is unlike many art forms in that we experience it every day: we've lived and worked in buildings our entire lives, beautiful and clumsy buildings, bare-bones and baroque, new, old, practical, and poorly designed. So when my team considered what tone to take in chatting with the Museum's already-architecture-savvy visitors, we aimed to be clear and informative, yes, but also direct and fun. Sure, let's look at Breuer's work closely and critically, but there's no need to peer down our noses.

The tour explores the variety of approaches to poured concrete on display and their technical requirements, including "bush-hammered" (left) and "board-form" (right). At left, the dark chips mixed into the concrete are obsidian.

Breuer was an intellectual, but we found that by navigating the architect's ideas and philosophical concepts through their visible construction, we could translate his theories into ordinary language. We sought out those specific details that display Breuer's ideas at play, and let you know where you can touch them. For example, Breuer spoke in somewhat grand terms about "humanizing" concrete, but what does that actually mean? The tour encourages you to take a close look in the lobby, where you'll discover for yourself the variety of different treatments Breuer applied to concrete. The range of surface textures brought out of this one substance—from the bush-hammered concrete on the lobby walls to the board-form concrete of the vestibule—directly illustrate Breuer's imaginative and elegant use of a material that's often damned as utilitarian or industrial.

Breuer's attention to detail and sense of experimentation are also visible throughout the building—once you know where to look. The tour explains what's special about the stairwell's teak banister capped with blackened brass, the bluestone pavers he darkened with pigmented wax, and the lobby's wall clock that he set in a custom-cast section of concrete. Listeners will also discover areas of construction where Breuer added chips of obsidian to catch the light—a luxe detail that might otherwise be overlooked.

Breuer originally designed the sunken garden as an indoor-outdoor space to display sculpture. When the plate-glass windows were installed in 1966, they were some of the largest in New York City.

Each of these elements has a particular purpose and story, and fits into Breuer's broader vision for the Museum. We invite you to listen in on a lively conversation among these experts plus Breuer himself, who speaks through archival audio clips drawn from a rare 1962 radio interview:

- Barry Bergdoll, Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History at Columbia University and co-editor of Marcel Breuer: Building Global Institutions;

- Jack Beyer, lead architect of the restoration and co-founder of Beyer Blinder Belle;

- Flora Biddle, former president of the Whitney Museum and granddaughter of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (founder of the Whitney);

- Brian Butterfield, senior design manager for exhibitions at The Met, who advised on the restoration;

- and Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Met.

The Met Breuer Architecture Tour is available on Audio Guide rental devices at the Museum, or for free online. Come have a listen as you sip a coffee in the sunken garden, or wait for a friend in the lobby. Or listen on the subway or while cooking dinner. We welcome your feedback, especially since your questions are where this whole tour began.

Related Content

Read more about the Bauhaus on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

Explore Frank Lloyd Wright's Francis W. Little House, an example of "organic architecture," in which the building, setting, interior, and furnishings are inextricably related.

Listen to more Audio Guides online.

Nina Diamond

Nina Diamond is an executive producer and editorial manager in the Digital Department.