Unrolling the Ceramic Canvases of Maya Painters

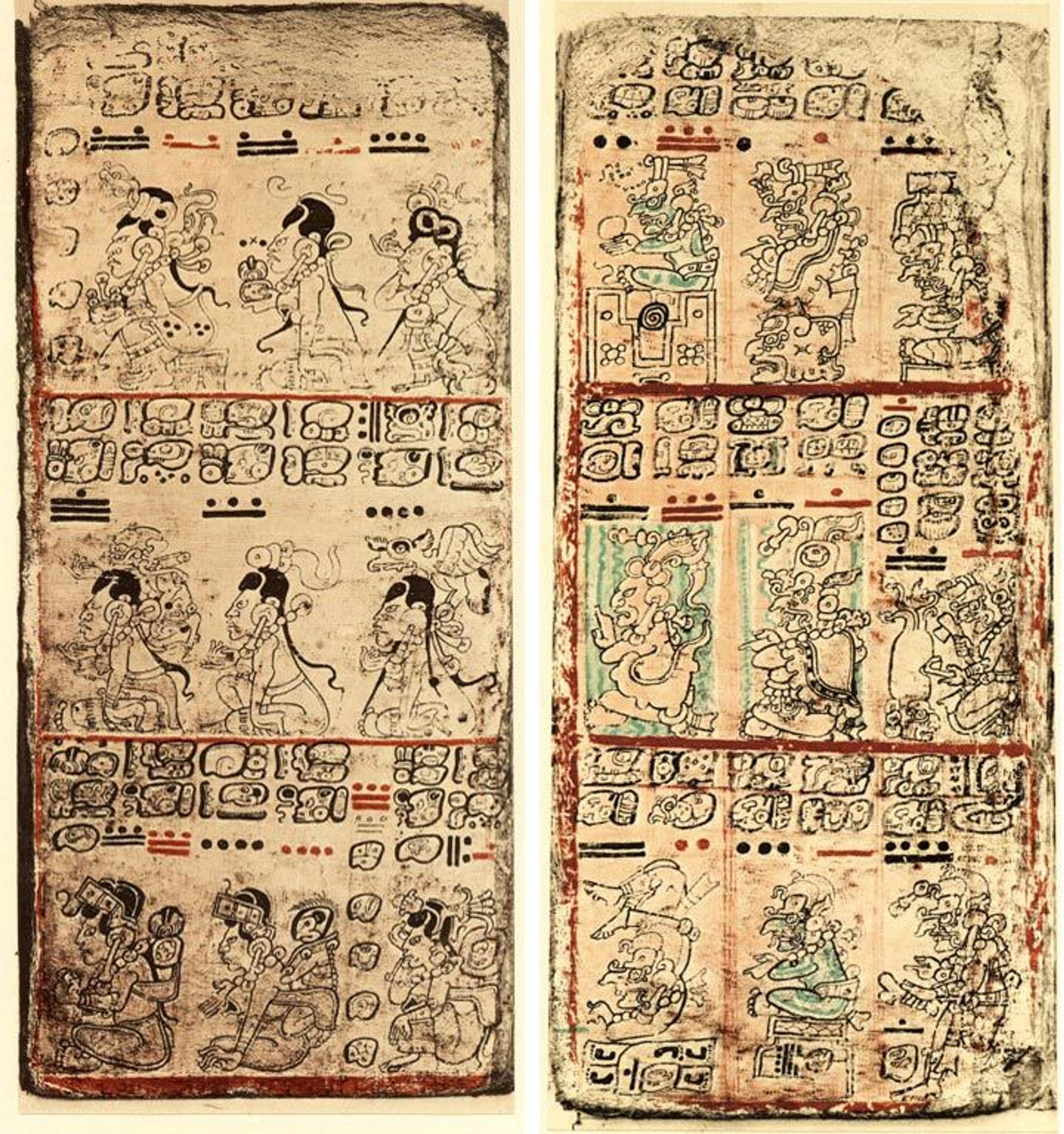

Fig. 1. Pages from the Dresden Codex (left: page 18; right: page 70), after facsimile editions by Ernst Förstemann, 1880, 1892. Sächsische Landesbibliothek Dresden, inv. Mscr. Dresd. R 310

«The master painters and scribes of the Classic Maya period (ca. A.D. 250–900) probably created hundreds, if not thousands, of illuminated books on bark paper or hide. These creations took the form of screenfold codices, only four of which survive from before the Spanish conquest. The 12th-century Dresden Codex—so named for its current repository at the State University Libraries of Dresden—is the best preserved, showcasing scenes of divine actions and tables of dates charting the cycles of celestial bodies.»

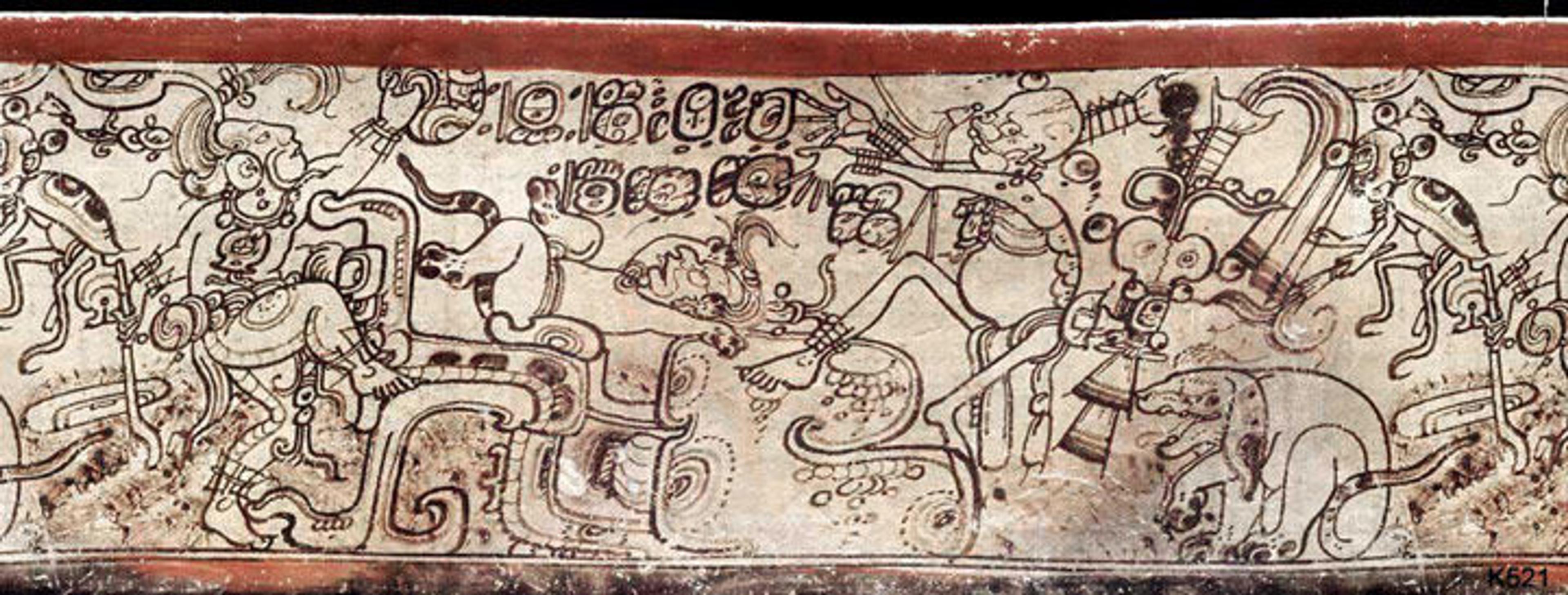

Because no complete books survive from the Classic period, scholars rely on scenes painted on ceramic plates and cylindrical drinking vessels in order to understand Maya visual narratives. When Michael Coe published the catalogue for his landmark exhibition The Maya Scribe and His World at the Grolier Club in 1973, he commissioned artist Diane Griffiths Peck to "roll out" the vessels using line drawings. Peck skillfully rendered the images from the cylindrical and globular vessels in planar form. Two of her drawings documented vessels now in The Met collection: the so-called "Metropolitan Vase" in the codex style, and a masterpiece stone pot for drinking chocolate (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Top: Vessel, mythological scene ("Metropolitan Vase"), 7th–8th century. Guatemala or Mexico. Maya, Late Classic. Ceramic with red, cream, and black slip, H. 5 1/2 (14 cm), Diam. 4 1/2 in. (11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Purchase, Nelson A. Rockefeller Gift, 1968 (1978.412.206). Drawing by Diane Griffiths Peck. Bottom: Spouted jar, 3rd–4th century. Guatemala or Mexico. Maya, Early Classic. Indurated limestone, H. 5 in. (12.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Charles and Valerie Diker, 1999 (1999.484.3). Drawing by Diane Griffiths Peck

Coe realized that these initial rollout drawings were time-consuming and would be costly to produce in the long term. To efficiently document the hundreds of Maya vessels that were known from archaeological excavations, in museum collections, and on the art market, a new method of photography was necessary to better roll out the scenes. This would not only capture the imagery in a legible way, but also allow for an unprecedented comparative study of hieroglyphic writing and painterly conventions.

Fig. 3. The Met's curators of the Ancient Americas and members of the Imaging Department meet with Justin Kerr and Michael Coe, August 2016. Photo by the author

Mike Coe teamed up with photographer Justin Kerr, who had an interest in the art of ancient Mesoamerica and had begun to photograph objects for various galleries in New York. Kerr began to research a process of creating Maya rollout photos using a variety of turntables and various camera apparatuses that allowed for the correct exposure. The goal was to turn the vessel and the film at the same rate in opposite directions so that the cylinder's scene would be unwrapped.

Fig. 4. Justin Kerr's rollout of the "Metropolitan Vase"

The first rollouts appeared in print for the Coe and Kerr collaboration Lords of the Underworld: Masterpieces of Classic Maya Ceramics, published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum. From the 1970s until the 2000s, Justin Kerr and his late wife, Barbara, produced hundreds of high-quality rollout photographs. It is hard to overstate the importance of their database in the advancement of scholarship on Maya art and hieroglyphic writing. To this day, discoveries in phonetic decipherment and art-historical studies happen because of the Kerr Maya Vase Database.

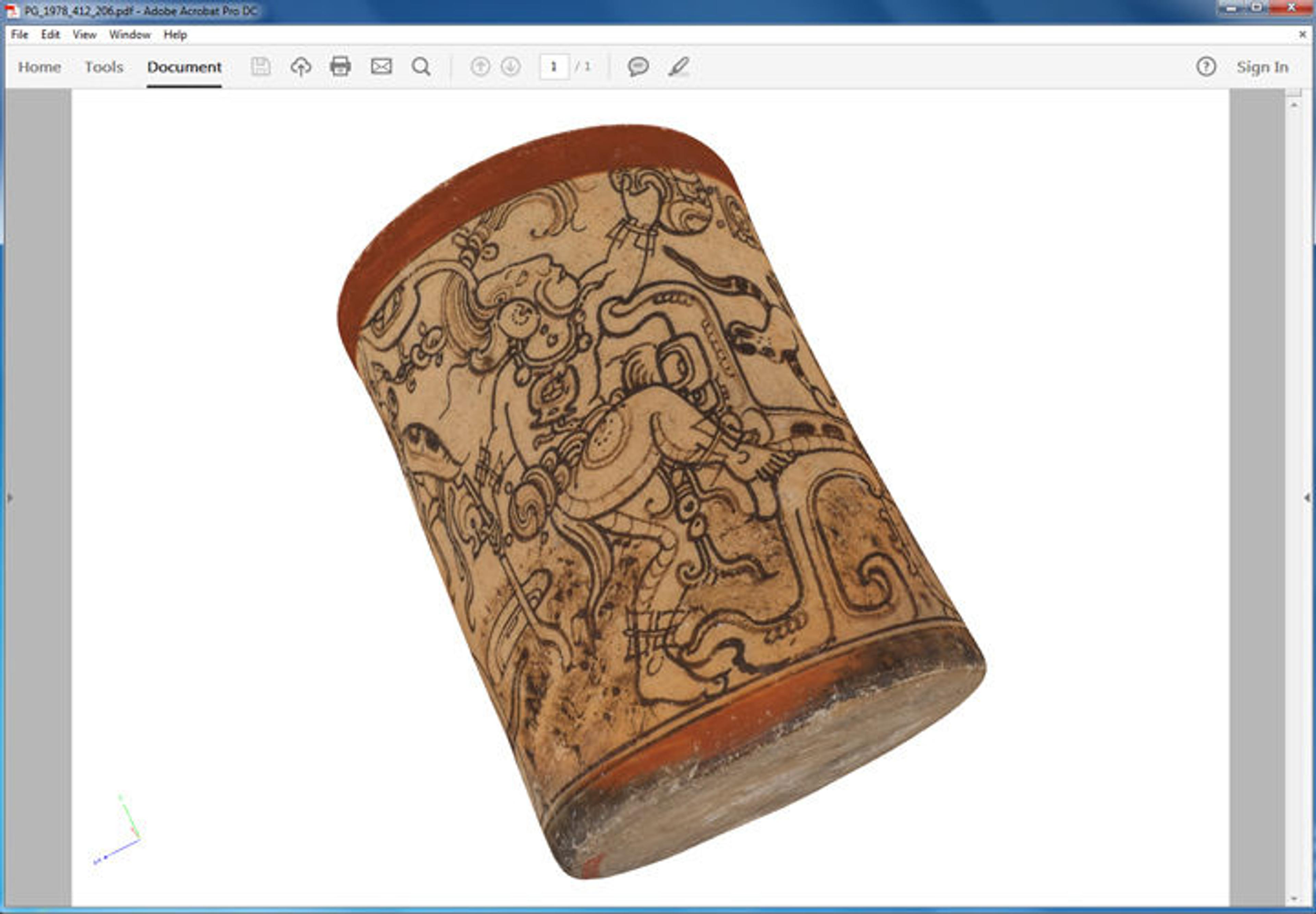

When I was preparing to publish an article in the upcoming volume of the Metropolitan Museum Journal on the codex-style Maya vases in The Met collection, the Editorial Department questioned whether it would be possible to produce new high-resolution, digital rollouts. The three main vessels featured in the article were sent to the Imaging Department, where two different approaches were tested specifically for this project: one similar to that used by Justin Kerr, and another taking advantage of three-dimensional imaging.

Fig. 5. Top: New rollout of the "Metropolitan Vase." Bottom: New rollout of vessel, mythological scene, 7th–8th century. Guatemala or Mexico, Mesoamerica. Maya, Late Classic. Ceramic with red, cream, and black slip, H. 4 1/2 in. (11.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller and Gifts of Nelson A. Rockefeller, Nathan Cummings, S.L.M. Barlow, Meredith Howland, and Captain Henry Erben, by exchange; and funds from various donors, 1980 (1980.213)

In the first method, Imaging Production Manager Thomas Ling devised a process that required taking 360 different photos exactly parallel to the painted surface. The vessel was placed on a turntable synchronized with the camera, which captured an image for every one degree of rotation (fig. 5). One advantage of this new method is that it allows for the curve, the rim, and the base of the vessel to be seen within the rollout. Even the T-shaped feet on The Met's small drinking cup are visible in the rollout, allowing scholars to see the entire object rather than just the painted body.

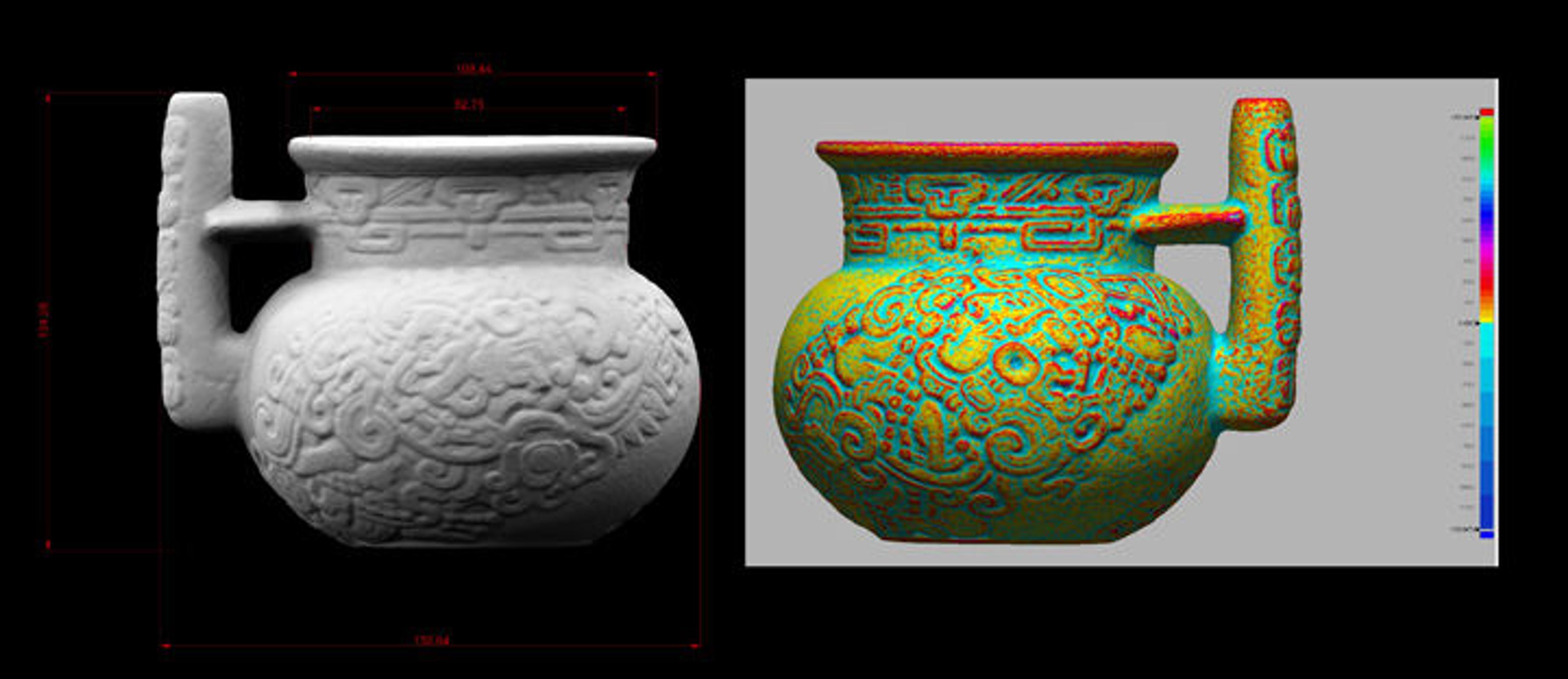

Fig. 6. Screenshot of a 3D model of the "Metropolitan Vase"

With the second method newly developed by Associate Imaging Specialist Dahee Han, Imaging Specialist Wilson Santiago, and Senior Manager of 3D Imaging Ronald Street, the Imaging Department team was able to deploy multiple software packages to create rollout scenes using a combination of computational photography, computer processing, and hand stitching. This method used photogrammetric methods as a primary data source to create the original three-dimensional models of the Museum's objects (fig. 6). By unrolling the captured 3D model, a new flat scene could be created as well. This method is more useful for capturing scenes more difficult to photograph as flat such as the chocolate vase mentioned above, which is decorated with low-relief sculpture (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. 3D models of the chocolate vase in false color. Photos courtesy of Ronald Street

Using these new technologies, we can now record and share the masterful canvases of Classic Maya vase painters and sculptors for publication in the Collection section of The Met's website, which is available to everyone for art-historical analysis, epigraphic studies, or personal inspiration.

Further Reading

Coe, Michael D. The Maya Scribe and His World. New York: Grolier Club, 1973.

Coe, Michael D., and Justin Kerr. Lords of the Underworld: Masterpieces of Classic Maya Ceramics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Doyle, James. "Creation Narratives on Ancient Maya Codex-Style Ceramics in the Met’s Collections." Metropolitan Museum Journal 51 (2016): 42–63.

Reents-Budet, Dorie. Painting the Maya Universe: Royal Ceramics of the Classic Period. Durham: Duke University Press, 1994.

James Doyle

James Doyle is an assistant curator in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

Follow James on Twitter: @JamesDoyleMet