The Portal of Villeloin-Coulangé at The Cloisters: Attribution After Eighty Years of Anonymity

Portal, 12th century. Made in Poitou or Santonge, France. Stone; Overall: 166 x 180 in. (421.6 x 457.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.878)

«Every curator, at one point or another, has to grapple with questions of provenance. In the case of medieval stone sculpture, works often come to us in fragmentary states, roughly removed from their original sites during revolutionary events, or cautiously salvaged from monuments that have not been cared for over time. Conservators, scientists, and art historians often collaborate to solve questions of geographic origin and attribution.»

The Romanesque portal at The Cloisters, above, was brought to the museum along with many monuments from the George Grey Barnard Collection. Shipped to New York sometime after 1922, it was first installed at the main entrance to his museum on Fort Washington Avenue (Husband, 12).

The portal installed at the main entrance to The Cloisters on Fort Washington Avenue, 1925 or 1926

Somewhat unreliable notes by Barnard, along with more serious art historical research, have associated the portal with a number of monuments in French Touraine, including the priory of Saint-Jean du Bas-Nueil (Letter from William Forsyth to Louise Dresser, May 25, 1967).

In 2000, in search for a positive identification, the Brookhaven National Laboratory took powdered samples from the portal to perform neutron activation analysis on them (Holmes and Harbottle, 24–27). The samples of stones were bombarded in a nuclear reactor to determine distinctive compositional patterns, or a "fingerprint." The concentrations of elements present in each sample of stone were then compared to data gathered from French quarries and monuments (Limestone Sculpture Provenance Project). At the time, a possible attribution to a location flattened by the French Revolution within the twelfth-century monastery of Notre-Dame d'Aiguevives was proposed, with reasonable matches between the two monuments.

The west portal of the twelfth-century monastery of Notre-Dame d'Aiguevives. Photograph by Lucretia Kargère

The attribution remained tentative, however, since the location proposed has been completely demolished, with no possibility for verification, and since, although a few powdered samples from Aiguevives were available, none was taken from the other possible sites of origin such as le-Bas-Nueil, or Montrichard (Nebelsztein and Fillion, 13–23).

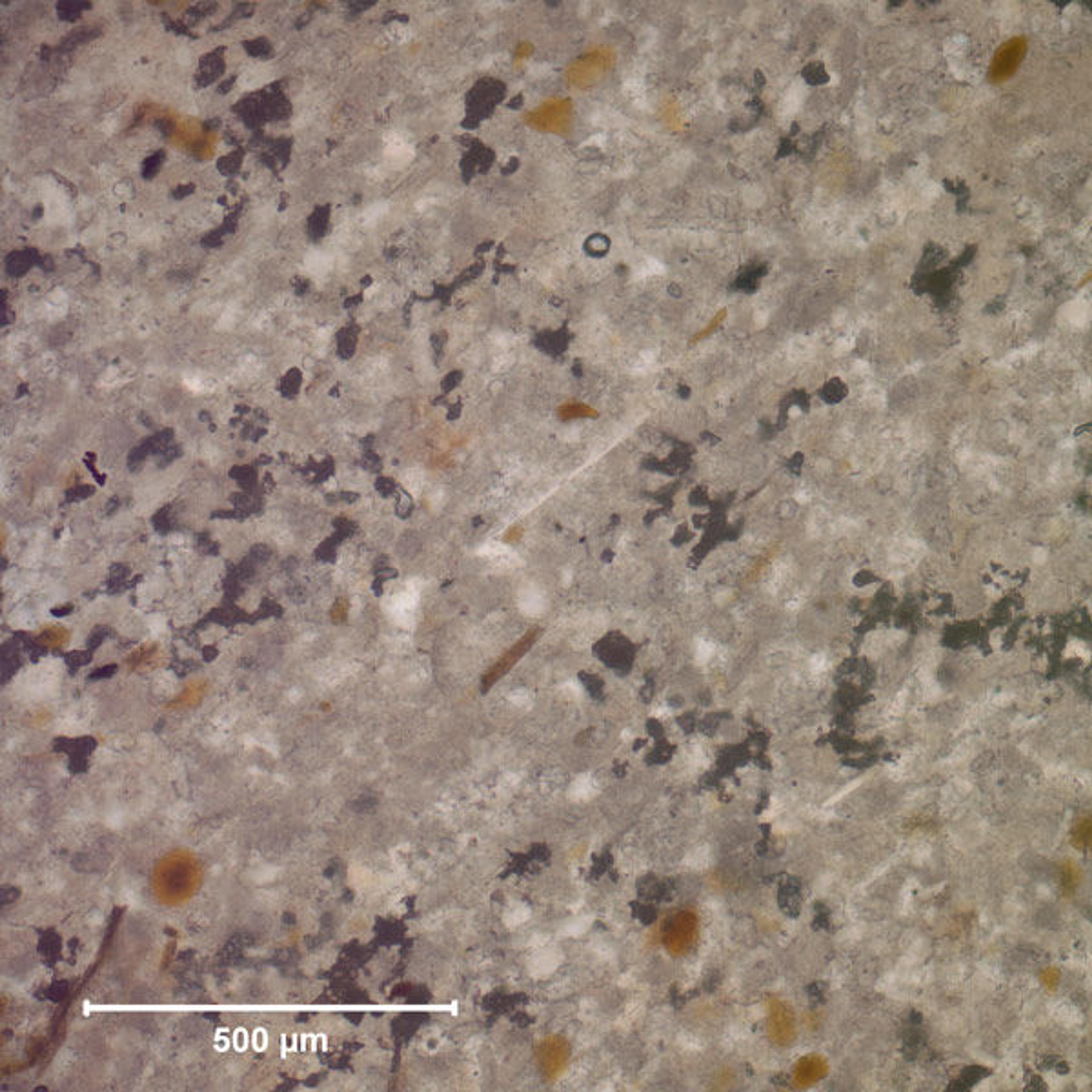

In 2010, thin-section analysis, coupled with XRD analysis, was performed for a better understanding of the stone properties and deterioration patterns. The Cloisters' portal is carved out of Tuffeau stone—a white limestone with a very fine particle size (granulometry), and a recognizable glow or sparkle—which was used for numerous monuments along the Loire River, notably the famous Castle of Chambord.

Thin section from the Abbaye d'Aiguevives, Tuffeau stone, transmitted light, cross-polar. Photograph by Federico Carò

The stone is highly porous (30 to 45%), and is in fact very sensitive to its environment, with alterations usually caused by water infiltration. In composition, it was found to have a low concentration of calcium carbonate (55%), with a significant concentration of quartz in the form of opal. Tests performed by Princeton University determined a low response to swelling with interaction with water (hygric swelling measurements).

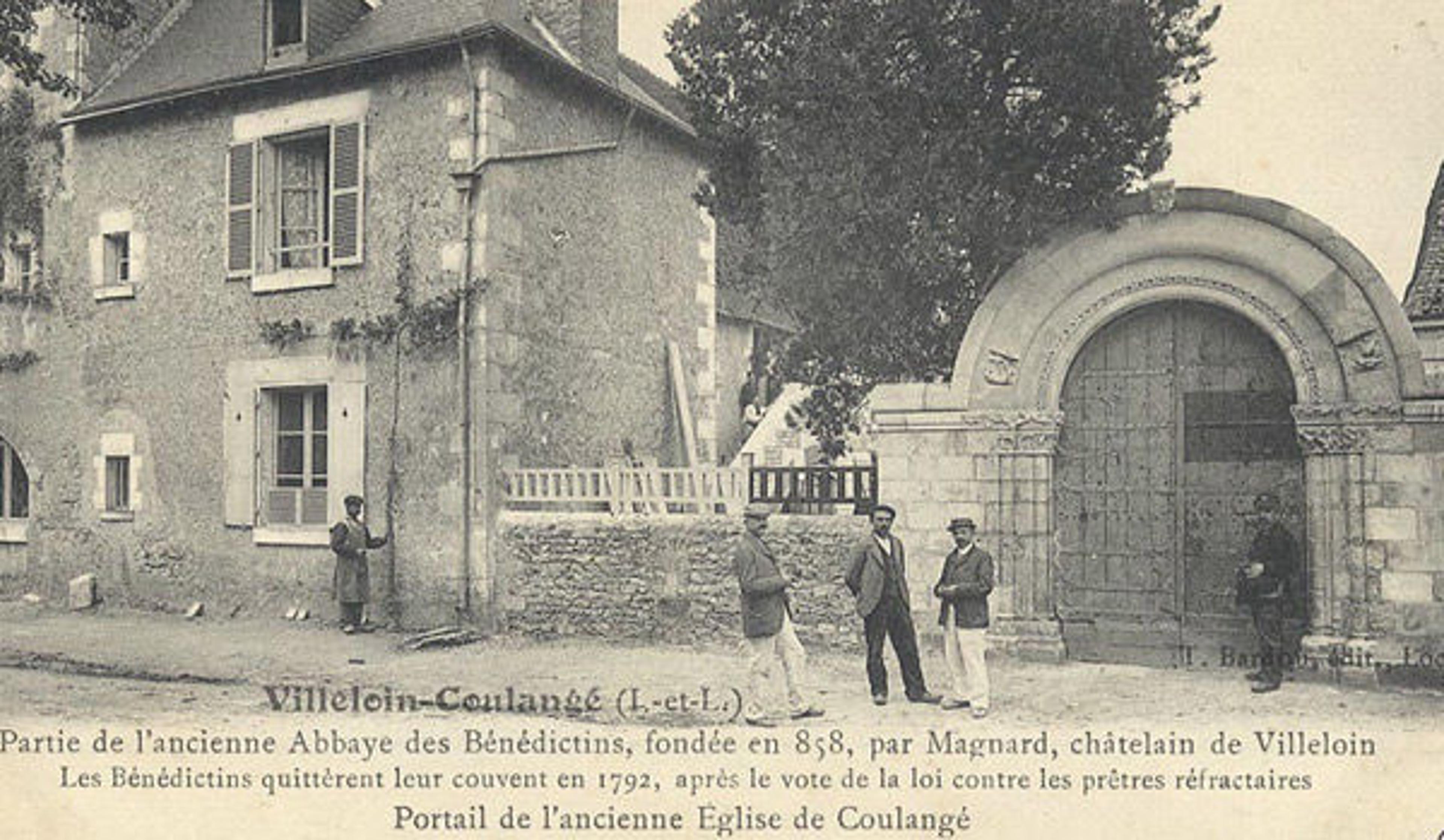

Extensive research in situ in 2012 brought the final answer to the investigation. We visited the many monuments under consideration, such Aiguevives and le-Bas-Nueil, and at each location closely examined both the stone material and carving styles. From the strong resemblance of what we saw to our portal (see the west portal of Notre-Dame d'Aiguevives, above), we knew we were closing in. The origin of the museum's portal was finally revealed by a happy encounter with an archaeologist and architectural historian of the French CNRS, whom we met on the trip when visiting an unrelated monument. After our meeting, he shared with us an old black-and-white postcard and asked, "Would you happen to know where the portal of this church is?"

The Romanesque Portal in Villeloin-Coulangé, undated postcard

The photograph showed our Romanesque portal as displayed in Villeloin-Coulangé (a commune that incorporated the villages of Villeloin and Coulangé in 1831), having been moved from its original location, the church of Saint-Sulpice in Coulangé, after the structure was sold to a private citizen in December 1844. As it turns out, Coulangé lies all but twenty-three kilometers south of Aiguevives.

Sources

Holmes, Lore L., and Garman Harbottle. "The Romanesque Arch at The Cloisters Museum: Stone Analysis," Gesta 19, no.1 (2000), pp. 24–27.

Husband, Timothy B. "Creating The Cloisters": The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin v. 70, no. 4 (Spring 2013).

The Limestone Sculpture Provenance Project. International Center of Medieval Art, 2004.

Nebelsztein, Virginie, and Benedicte Fillion, "Le portail no.25/120/878 du Musée des Cloitres: une nouvelle attribution," Gesta 39, no.1 (2000), pp. 13–23.

Worcester Art Museum Archives. Letter from William Forsyth to Louise Dresser, May 25, 1967.

Lucretia Kargère

Lucretia Kargère is a conservator at The Met Cloisters.

Nancy Wu

Nancy Wu is a Museum educator at The Met Cloisters.