Returning a Museum Treasure to the Limelight for Bach's Goldberg Variations

«Despite its immense popularity in the worlds of both classical music and pop culture, Johann Sebastian Bach's Goldberg Variations is actually not a work that is regularly performed or recorded. A seminal statement of Baroque keyboard composition, the sprawling, seventy-minute collection of an aria and thirty variations remains a heralded benchmark of technical virtuosity and musical intelligence for which few pianists confidently rise to the occasion. Even soloist Jeremy Denk, one of the most respected pianists on the global concert circuit today, remarked that "the Goldberg Variations have caused me more misery than any other piece of music in history . . ." However, New York audiences have a chance to encounter this masterwork right here at the Met on November 21, when pianist Christopher Taylor presents The Goldberg Variations: The Double Manual Experience in the Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium.»

Left: Christopher Taylor. Photo courtesy of the artist

Many aspects of the Goldberg Variations are shrouded in mystery—including the rationale behind the composition's nickname and the origin of the aria, the bass line of which forms the architecture for each of the thirty variations that follow. Long thought to have been composed for Johann Gottlieb Goldberg—a musician employed by the Russian ambassador Count Kaiserling in the electoral court of Saxony, who was thought to have commissioned the work for Goldberg to play during the Count's many sleepless nights—this origin tale has actually long been debunked, leaving the title to be interpreted ambiguously at best. Additionally, the aria itself cannot be traced directly to Bach, with the only autograph version of the thirty-two-measure preamble appearing in the handwriting of Bach's second wife, Anna Magdalena, in one of her personal notebooks.

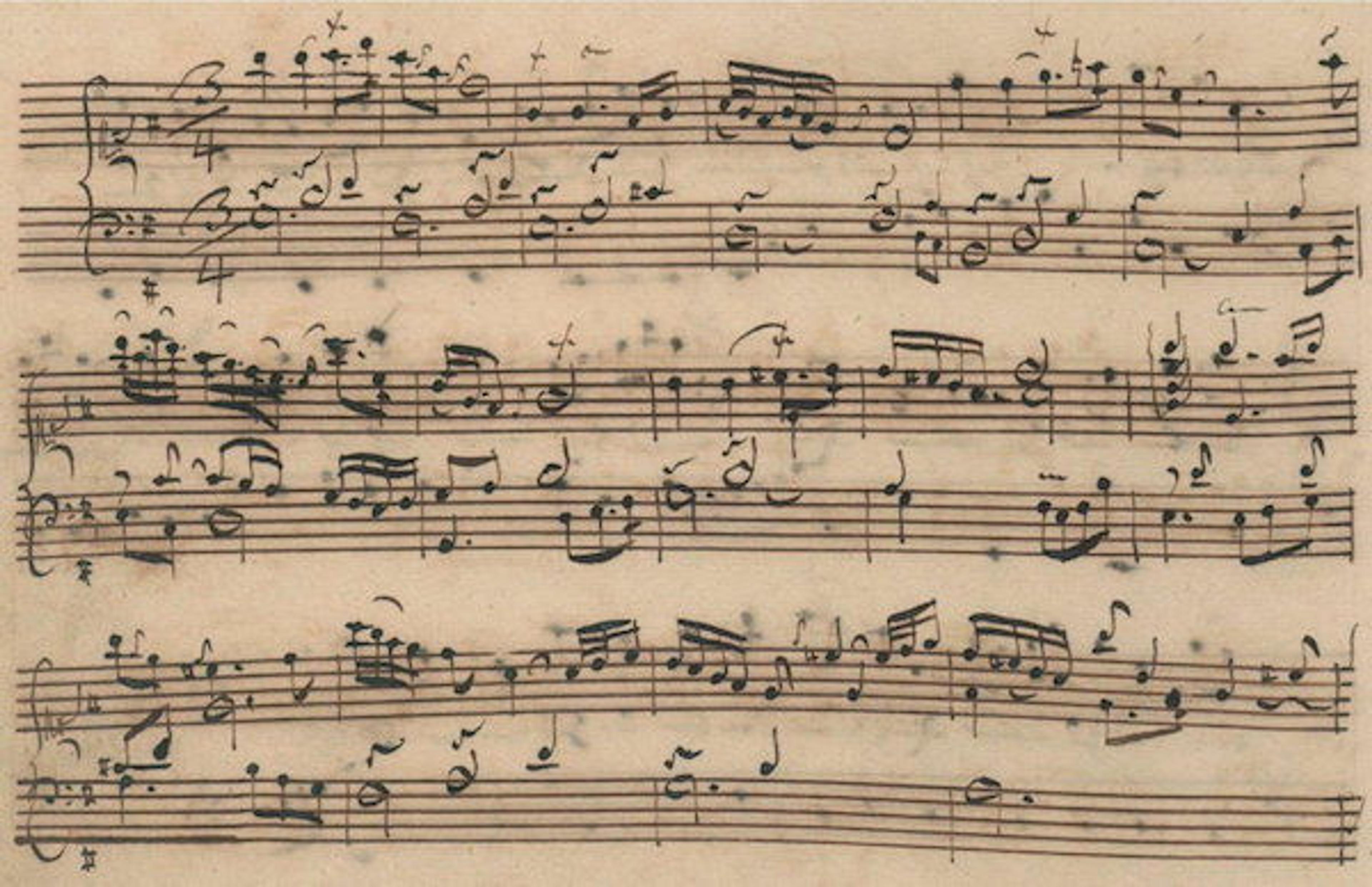

A handwritten copy of the Goldberg Variations aria, from the notebook of Anna Magdalena Bach, 1725

However, what does remain is the work's legacy as one of the most ambitious and difficult compositions ever written for the harpsichord—specifically a double-manual (or keyboard) instrument. In its length it eclipses even the large-scale orchestral compositions of the time, and in terms of sheer dexterity it demands much of the performer: Each variation maintains a unique character through the use of varying time signatures and musical styles ranging from elegant sarabandes to staunch French overtures. There are incredibly problematic hand crossings and fiendishly difficult voicings that are exacerbated even more by the modern-day practice of performing the work on a single keyboard.

Because of the variations' demands on a single-keyboard instrument and a desire to present the work in its intended form, pianist Christopher Taylor, who has become well known for his interpretation of the Goldberg Variations, will perform the work in its original version on a two-manual instrument—specifically, a rare example of a double-manual piano that has been on loan to the Met since 1947. One of only sixty such instruments ever produced, the Museum's Bösendorfer was built with 164 keys—the standard 88 on the lower keyboard and 76 on the upper—in a design developed by the Hungarian composer and inventor Emanuel Moor. To aid the performer in using both keyboards, the lower manual's keys have raised backs (shown below), which allow the pianist to simultaneously play both keyboards with one hand; the keys of the upper manual are crafted in the standard shape. And, because the upper keyboard is tuned to play one octave above its analogous keys on the lower manual, passages needing difficult octave work are made easier through the use of an additional pedal that can activate both the upper and lower octave's hammers at once.

Grand piano with double keyboard, ca. 1940. Bösendorfer; action by Emanuel Moor. Vienna, Austria. Various materials. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Loaned by Winifred Christie Moor, 1948 (L.48.4)

Moor's design was initially thought to be unrealistic from a manufacturer's perspective, but was finally adopted for a brief period of time by Bösendorfer, Steinway, Chickering, and Bechstein, albeit in very limited numbers. The Met's Bösendorfer, originally owned by Winifred Christie Moor (Emanuel's wife, herself a well-known pianist and advocate of the double-manual design), was given to the Met as an indefinite loan in 1947, and subsequently confirmed as a permanent loan by the trustees of Moor's estate in 1968.

Detail view of the Bösendorfer's nameplate and keyboard showing Moor's raised-key design

For decades, the piano lived in the office of the then-curator of the Department of Musical Instruments, Emanuel Winternitz. The current head of the department, Frederick P. Rose Curator in Charge of Musical Instruments Ken Moore, fondly remembers the piano's important place in Winternitz's office while working with the former curator during his student days. Christopher Taylor's upcoming performance marks the first time the Bösendorfer will be seen by the public since Winternitz's retirement in 1973, and it has recently undergone extensive tuning and diagnostic checks in preparation for this unique performance on November 21.

To purchase tickets to The Goldberg Variations: The Double Manual Experience or any other Met Museum Presents event, visit www.metmuseum.org/tickets; call 212-570-3949; or stop by the Great Hall Box Office, open Monday–Saturday, 11:00 a.m.–3:30 p.m.

Related Link

Of Note: Celebrating National Piano Month

Michael Cirigliano

Michael Cirigliano II is the managing editor in the Digital Department.