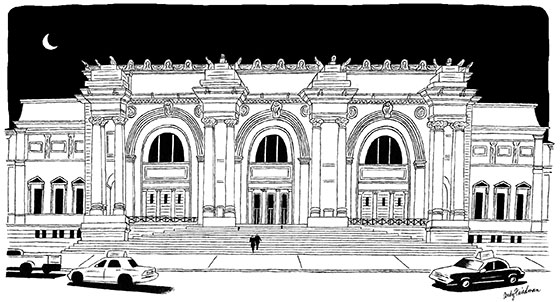

My wife and I have a long-standing Friday-night date at the Met, which is open till 9 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays. The museum is really quite different then. The tourists have cleared out; the place is calmer and harks back to another time when museums were mysterious rather than bustling. We spot regulars and smile at them in the secret knowledge of how special this is. Our regular routine involves stopping into the subterranean cafeteria and splitting a black-and-white cookie. Or we’ll check out the elegant bar located above the Great Hall, which features live chamber music during the evenings. That, combined with clinking dishes echoing off stone, conjures Venice’s Piazza San Marco.

As with Venice, as soon as you get away from the main thoroughfares you’ll find yourself almost alone, spellbound with wonder. At night the light is different too, softer; the time you spend in front of the works is more special, less jostled. The Met is so gigantic and dense. Sure, you can follow a preplanned route, but also let your wandering eyes tell you where you need to go. On every visit I either stumble on something I never noticed before or see something I’ve seen a hundred times in a totally new light. Here’s a rudimentary itinerary to get you started.

I was going to point you to Egypt, but then I got stuck for more than a half-hour on the first sculptural case inside the door—a number of stone axes in Gallery 101. Some were carved around 300,000 years ago by an extinct species of proto-humans, Neanderthal man.

For our purposes, go left inside the main entrance and into the glories of ancient Greece and Rome. Usually this wing is packed. Not at night. Sorry to be a drama queen, but I almost lost it again at the first case inside this entrance: a headless, footless stone nude female figure carved in 4500–4000 B.C. (Gallery 150). You are seeing the exact moment our species was coming out of its final Neolithic consciousness into something else. Enormous thighs and derrière, wonderful rolls of belly fat, small breasts, arms folded across chest make this a wonder of minimal elegance, carving, solidity. It could be anything from a fertility figure to a doll to a goddess. I prefer to imagine it carved by women for women.

Across from this gallery is another, Gallery 152, with objects made in Greece. Here, every helmet, water jar, mixing bowl, and drinking cup lets a world come into focus. Alone in these rooms, you can project yourself into Homeric odysseys. This only sharpens as you move through the galleries. Soon you’re seeing Roman sculpture, which basically tweaks Greece in fabulously mad artistic directions. Don’t miss some of the most beautiful butts in all the Met here.

You could spend a lifetime in these galleries. Instead, head into the large Rockefeller Wing. But wait. Just inside the entrance, in a teeny alcove, is one of my top-ten favorite objects in the Met (Gallery 351): a large Ethiopian illuminated Gospel from the late-fourteenth or early-fifteenth century. Take a breath and enter the Rockefeller Wing. Prepare to be laid low by the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. In Gallery 350 is a caked, monochromatic brown bovine form, known as a boli. Made in Mali, it is fashioned from wood and “sacrificial materials,” including chicken blood, and exudes tremendous power.

Take a left into the galleries of Oceanic art, Gallery 354, to see some of the best, most abstracted, sexiest wooden figurative sculpture in the world. There are often lovers sitting here. You can see why when looking at the multiple vulvas and penises. After you regain your composure, wind around to the various galleries. I did and found myself alone with a brand-new case of prehistoric ceramics made in the present-day Southwest (Gallery 356). Ogle the delicately painted vessels and bowls with geometric landscapes and figures. These were typically placed over the faces of buried bodies; note the hole in every one, a place for the spirit to be released. Swoon at two men climbing a tree where a bird is perched, or a swarm of little tadpoles swimming in a pond the shape of a bobcat head.

From here, walk straight ahead into the many galleries of modern and contemporary art. The Met gets about 50 centuries of art absolutely perfect. Not so with the past century. Nevertheless, with excellent bequests from the likes of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, you’ll behold some of my favorite twentieth-century artists. I’ll leave you—probably alone—in one gallery (908), which has four of the most visionary paintings in the museum: Florine Stettheimer’s “Cathedral” series where she celebrates shopping, art, artists, art critics, and Henri Bendel. Across the way are four canvases by my favorite twentieth-century American painter, Marsden Hartley.

From here you’re on your own. Oh, wait! Don’t forget the Horace Pippin a couple rooms from here, Gallery 911. Look for us in the cafeteria. We can all compare notes and you can tell me where to go.