Exploring Persian Literature in Bazm and Razm

Gallery view of Bazm and Razm: Feast and Fight in Persian Art, on view through May 31. Photo courtesy of the author

«Last year as I helped a curator in the Department of Islamic Art prepare for the exhibition Bazm and Razm: Feast and Fight in Persian Art, I thought about what information we would be able to provide about the paintings and objects on display, and how much we would have to leave out. Iran has an incredibly deep and complex literary tradition that draws influence from a range of sources, including epic poetry, romances, and mystical works. While it would be impossible to give a complete introduction to the literature of Iran, this exhibition provided an opportunity to highlight some key works and familiarize visitors with these stories.»

Many of our visitors may be familiar with the tale of One Thousand and One Nights, but fewer know the names of the most influential Persian works—the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Abu'l Qasim Firdausi, the Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami, and the Mantiq al-Tair (Language of the Birds) of Farid al Din 'Attar. Included in the department's collection is a set of seventy-six folios from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp. This manuscript, completed in the first half of the sixteenth century, is one of the most luxurious editions of the Shahnama known to exist; its large format, extensive use of gold and silver, and the quality of craftsmanship that went into the calligraphy and paintings mark it as an exceptional work.

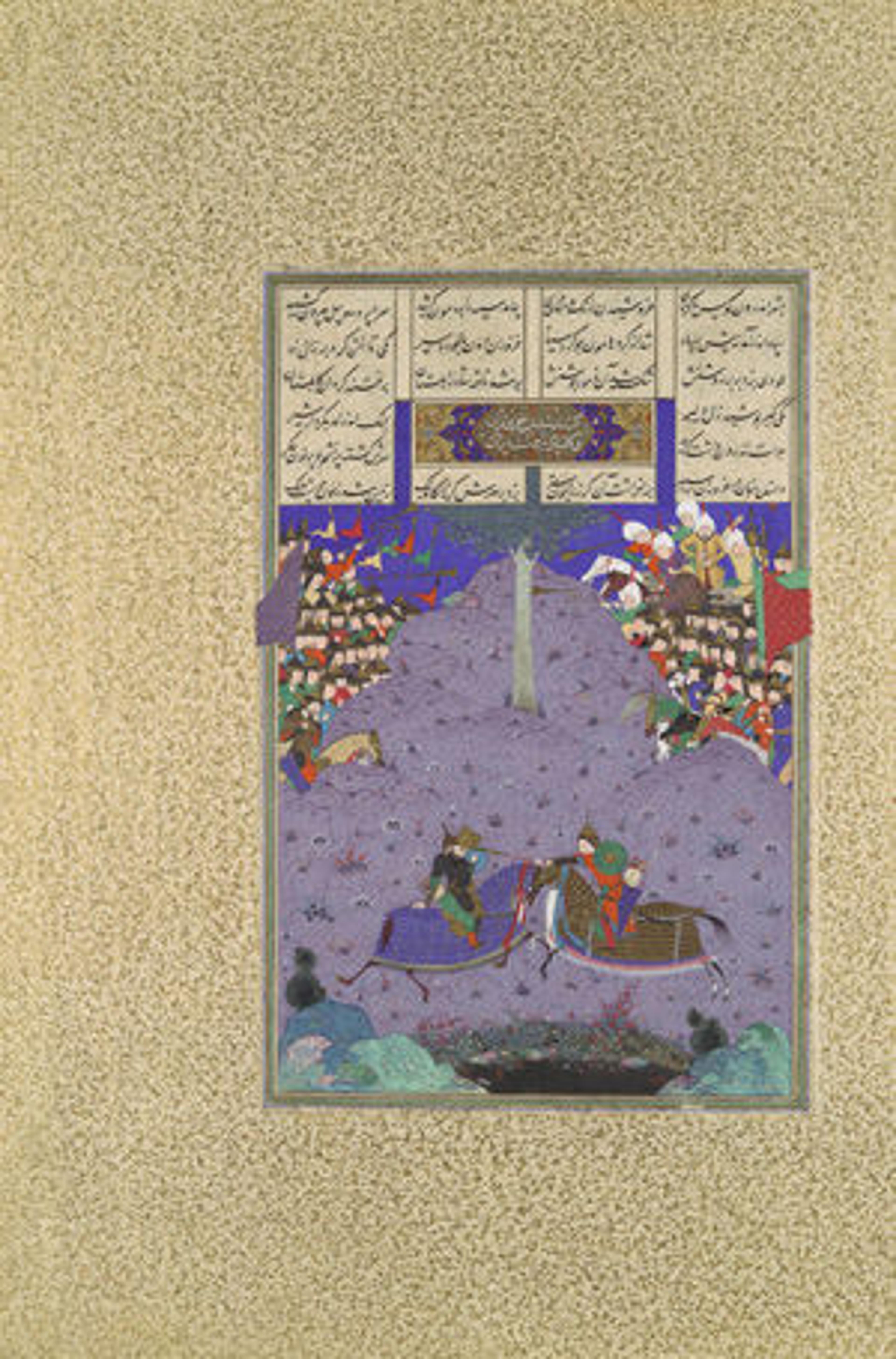

Left: "Zal Slays Khazarvan," Folio 104r from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, ca. 1525–30. Iran, Tabriz. Islamic. Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Arthur A. Houghton Jr., 1970 (1970.301.15)

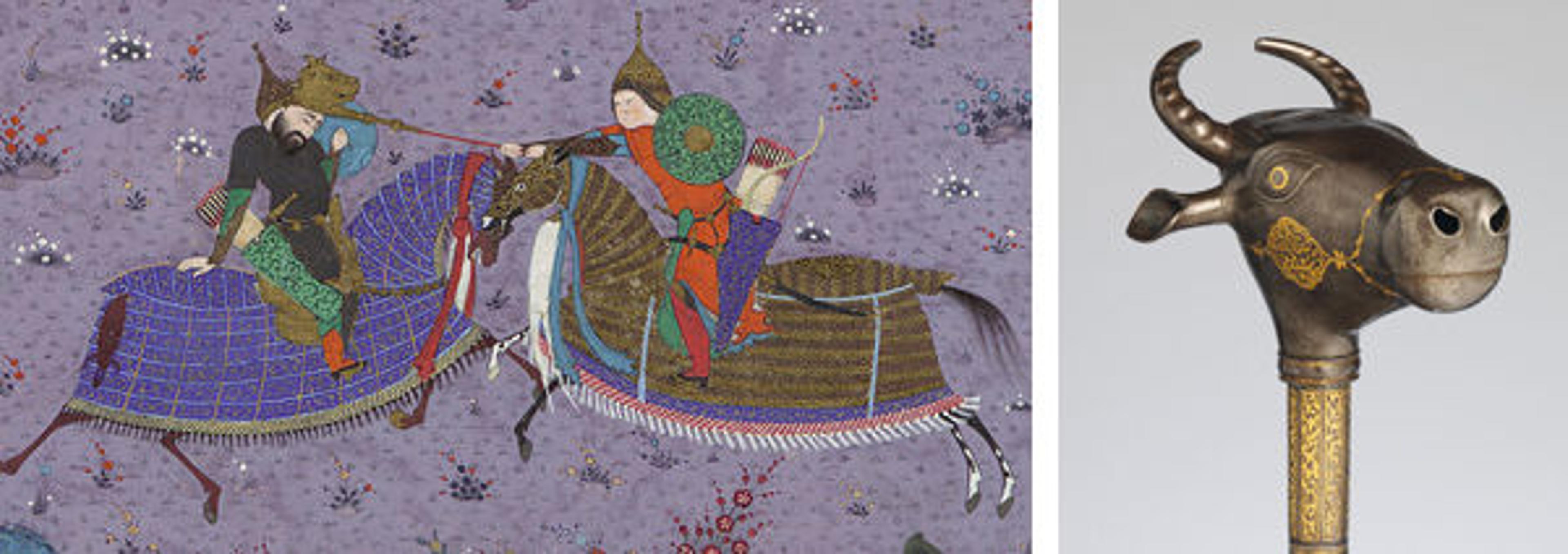

The three folios from this manuscript on view in the exhibition were chosen for the objects depicted within them in addition to their fine quality and the richness of the stories they tell. A painting in which the legendary hero Zal uses his ox-head mace to kill a Turanian enemy is paired with an actual ox-head mace from the Department of Arms and Armor that was made several centuries later, under the Qajars. Across the room, another scene from the manuscript depicts a meeting between Shah Manuchihr and his former guardian, Sam. While the story itself is fascinating, the exhibition focuses on what we can learn about the material culture and royal life of sixteenth-century Iran by displaying the folio alongside ceramic and metal objects similar to those depicted in the painting.

Left: Detail from "Zal Slays Khazarvan." Right: Mace (detail), 19th century. Persian. Steel, gold, L. 32 1/2 in. (82.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George C. Stone, 1935 (36.25.1882)

It can be even more complicated to convey the plots and meaning behind other canonical works. Take, for example, the Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami. This collection of five stories, written in the format of rhyming couplets, includes several of the same characters as those in the Shahnama, although the stories themselves differ. Bahram V, also known as Bahram Gur for his skill at shooting onagers (gur in Persian), appears in the Shahnama as well as in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses) of the Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami. The structure of the Haft Paikar lends itself particularly well to the medium of miniature painting. In this story, Bahram Gur marries seven princesses, one from each of the seven regions of the world. He visits each princess in her own pavilion on successive nights of the week. Stories within the larger plot differ, but the repetition of the seven princesses, regions, nights, and pavilions provides structure to the tale and its illustrations.

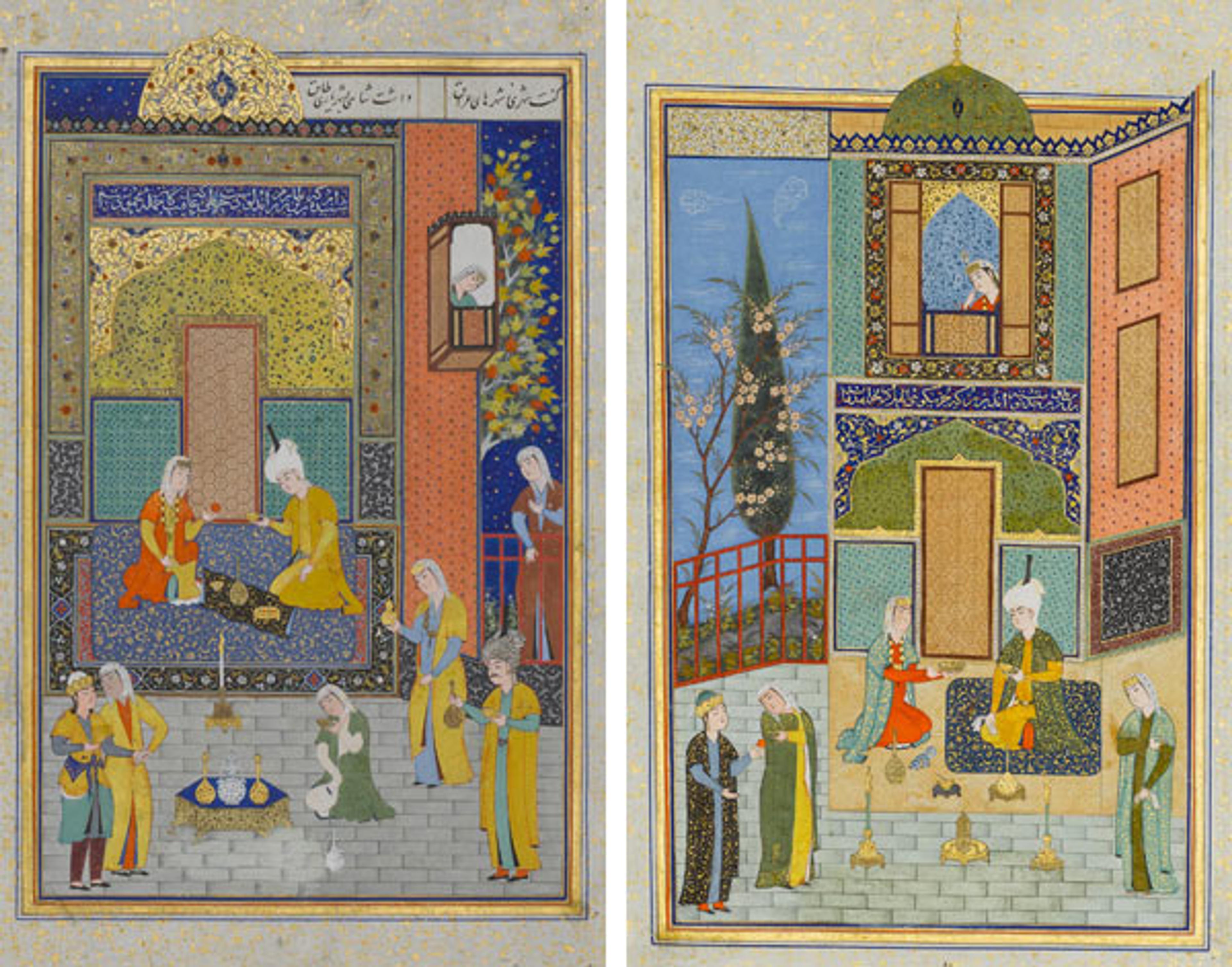

Left: "Bahram Gur in the Yellow Palace on Sunday" (detail), Folio from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami, A.H. 931/A.D. 1524–25. Present-day Afghanistan, Herat. Islamic. Ink, opaque watercolor, silver, and gold on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1913 (13.228.7.9). Right: "Bahram Gur in the Green Palace on Monday" (detail), Folio from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami, A.H. 931/A.D. 1524–25. Present-day Afghanistan, Herat. Islamic. Ink, opaque watercolor, silver, and gold on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1913 (13.228.7.12)

These two folios from a 1524–25 manuscript of the Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami depict two consecutive nights in the Haft Paikar. In the painting on the left, Bahram Gur visits the princess of Rum (based on the Persian word for Rome) in her yellow pavilion. On the right, he visits the princess of Khorezm (in Central Asia) in her green pavilion. The repetitive structure of the story lends itself well to these paintings in which elements of the architectural settings, the posing of figures, and the food and objects are all repeated in the different paintings.

While the exhibition Bazm and Razm is drawing to a close, the permanent Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia are full of opportunities to continue exploring the literature of the region.

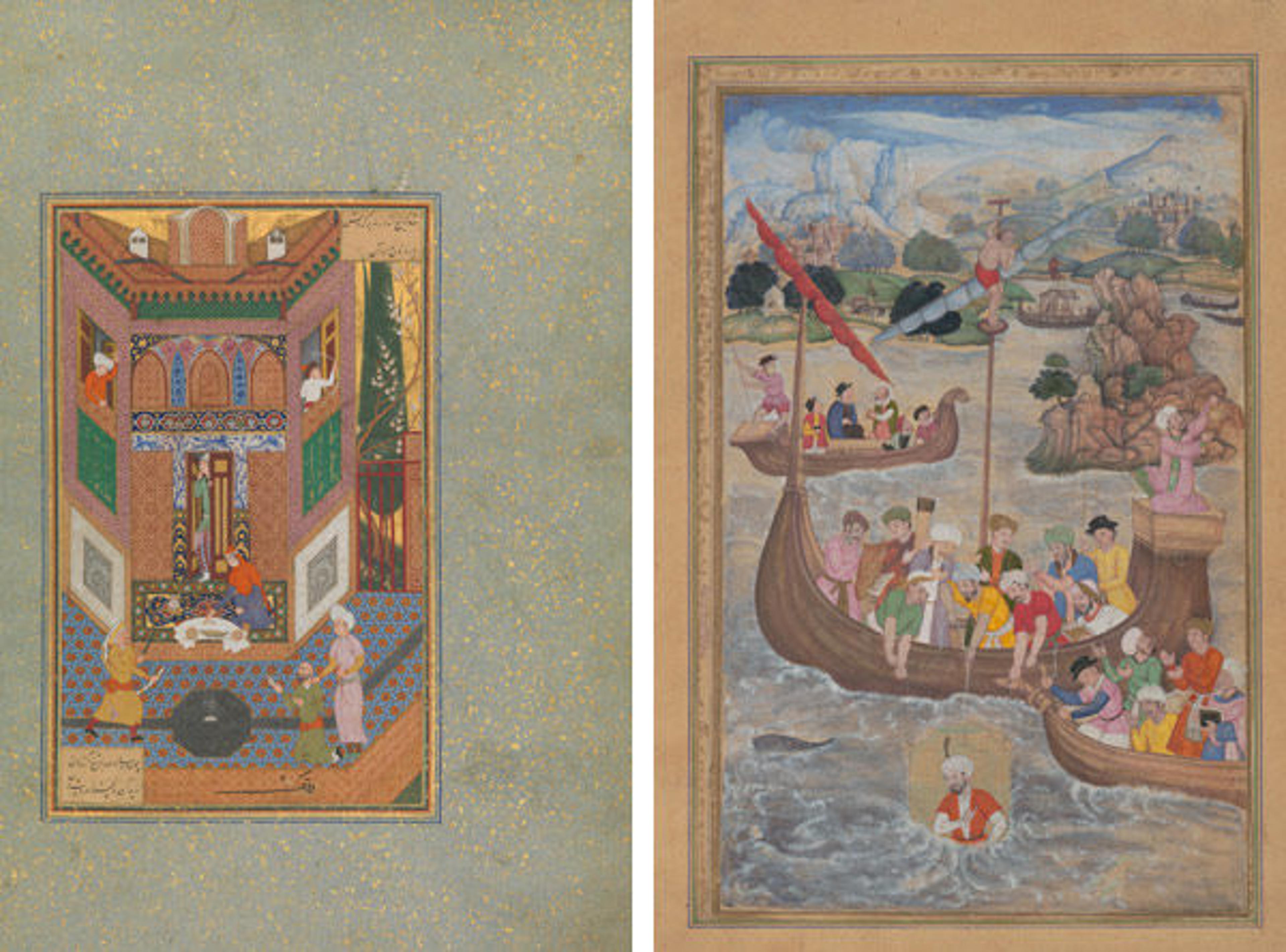

Left: "A Ruffian Spares the Life of a Poor Man," Folio 4v from a Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds) of Farid al-Din 'Attar, ca. 1600. Iran, Isfahan. Islamic. Ink, opaque watercolor, silver, and gold on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1963 (63.210.4). On view in gallery 455. Right: "Alexander is Lowered into the Sea," Folio from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Amir Khusrau Dihlavi, 1597–98. India. Islamic. Ink, watercolor, gold on paper: Gold on dyed paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1913 (13.228.27). On view in gallery 463

Related Links

Bazm and Razm: Feast and Fight in Persian Art, on view February 17–May 31, 2015

Now at the Met: Celebrating Nauruz with The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp

MetPublications: The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp: The Persian Book of Kings (2014)

Julia Cohen

Julia Cohen is a research assistant in the Department of Islamic Art.