Former Incarnations: The Secret Lives of Objects in Treasures from India

«Works of art at the Met are often presented in isolation to give the viewer an opportunity to examine them closely and appreciate their artistic merit, fine craftsmanship, use of materials, and other details. Because of these objects' (near) impeccable state when exhibited, I sometimes forget they have lived entire lives before arriving at the Museum and often have passed through many hands and traveled long distances. Indeed, the life of an object is so much richer, more complicated, and more convoluted than its shining presence in a display case can convey.

While researching the objects selected for the exhibition Treasures from India: Jewels from The Al-Thani Collection (on view through January 25, 2015), I was continually inspired by these histories and fascinated by the winding paths these works had taken before their arrival in our galleries.»

A few examples particularly illustrate this point. Take for example, a large sarpesh, or turban ornament made of gold, diamonds, and hanging spinels. The sarpesh was produced in early nineteenth-century Hyderabad, which is in the Deccan region of South India.

Turban ornament (sarpesh), 1800–50. South India, Hyderabad. Gold, set with diamonds, with hanging spinels of earlier date; enamel on reverse. The Al-Thani Collection. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

One of the spinels is of particular interest, as it is inscribed with the name and dates of the seventeenth-century Mughal Emperor Jahangir, as well as the title and dates of his son, Shah Jahan, both of whom reigned in North India.

Spinel from the sarpesh. Inscriptions on the spinel read: "Jahangir Shah (son) of Akbar Shah / 1016" (which corresponds to the year A.D. 1607–8) and "1043 / Second Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction / 6" (which corresponds to the year A.D. 1633–4). The number 6 here refers to the sixth year of Shah Jahan's reign. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

The tiny inscription dates the spinel to some two hundred years earlier than the sarpesh. It's fun to imagine how this one inscribed gem would have originally been set into a completely different piece of jewelry—maybe a necklace, or a jigha—and passed down from father to son in the royal Mughal court. When did it leave Shah Jahan's possession? Who attached it to this sarpesh centuries later?

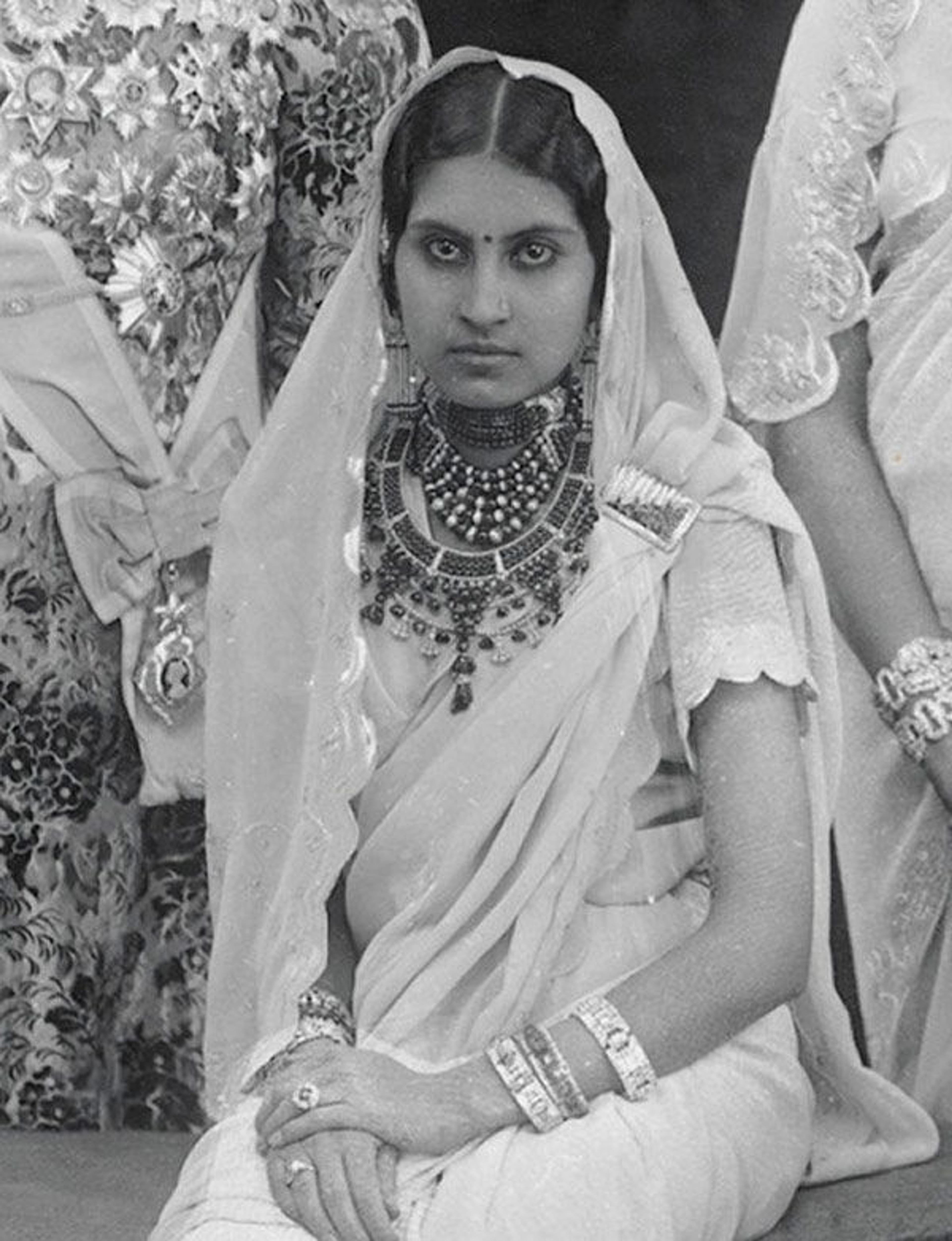

Objects can disappear for years before reemerging, and we may never know their history during that time. In another example, the necklace that has come to be known as the Patiala Ruby Choker was originally made by Cartier for the Maharaja of Patiala (r. 1900–38), who gave it to one of his wives in 1931. She wears it in this photograph as part of an ensemble of three ruby necklaces, all designed by Cartier.

Maharani wearing Cartier necklaces, including the ruby choker (detail), 1931. © National Portrait Gallery, London

At some point, this necklace became disbanded. When and why it left the Patiala royal family is a mystery. What is known is that when it appeared on the Swiss art market in 2000, the object had been shortened and was consigned as a bracelet. The pearls and about ten centimeters of rubies had been removed, but the Cartier signature on the reverse remained intact.

Recognizing this important historical piece, Cartier Paris purchased and restrung the object in its original configuration, the form in which it once again appears.

The Patiala Ruby Choker, 1931; restored and restrung to the original design by Cartier Tradition, Geneva, 2012. Rubies, diamonds, and pearls, with platinum mounts. The Al-Thani Collection. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

The individual rubies and diamonds have an even longer history, as these gems were given by the Maharaja to Cartier to rework, and had been in his family for generations. If only we could know what other jewelry they adorned before 1931!

The famous jewel known as the Taj Mahal Emerald went through a similar disappearance before reemerging.

Taj Mahal Emerald. The Al-Thani Collection. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

In 1925, this hexagonal gem formed the centerpiece of the Cartier neck ornament known as the Collier Bérénice, which was displayed at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris.

A mannequin models the neck ornament with the Taj Mahal Emerald, and other jewelry (detail). Archives Cartier Paris. © Cartier

After the exposition, the jewels in the neck ornament were disassembled. The Taj Mahal Emerald was mounted into a brooch before being detached once again and passed through several private owners in Europe, who likely were unaware of this Cartier connection. In the 1980s, the gem resurfaced in New York City's Diamond District on 47th Street, and remained in the possession of a private gem dealer who exhibited the emerald in the exhibition Romance of the Taj Mahal (1990–91), organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In the late 1990s, jewelry historian Michael Spink uncovered a historical photograph clearly showing the Collier Bérénice emeralds, which allowed him connect the Taj Mahal Emerald to its Cartier history. The gem has since been celebrated for this important provenance. The whereabouts of the other large carved emeralds from the Collier Bérénice remain unknown.

One of the stars of the Al-Thani Collection is the tiger's head finial from the throne of Mysore ruler Tipu Sultan (r. 1782–1799).

Finial from the throne of Tipu Sultan, ca. 1790. South India, Mysore. Gold, inlaid with diamonds, rubies, and emeralds; lac core. The Al-Thani Collection. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

This stunning ruby, diamond, emerald, and gold object originally was one of eight similar finials that ornamented Tipu Sultan's magnificent royal throne. When the British sacked Seringapatnam in 1799 and Tipu Sultan was killed, the throne was destroyed and some pieces, like this one, were captured as booty.

Looking closely at the base of the tiger's head, you can see the uneven way in which the ornament was severed from its original setting.

Finial from the throne of Tipu Sultan (detail), ca. 1790. South India, Mysore. Gold, inlaid with diamonds, rubies, and emeralds; lac core. The Al-Thani Collection. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

This souvenir was taken back to England, where it passed through a few private collections before traveling to Canada in about 1833, where it lived in another private collection until 2009. Sometime in the nineteenth century, the head was placed atop the mount on which it presently sits, which is further ornamented with claw feet and a stepped plinth.

Finial from the throne of Tipu Sultan, ca. 1790. South India, Mysore. Gold, inlaid with diamonds, rubies, and emeralds; lac core. The Al-Thani Collection. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

The front of the base contains a fragmentary, illegible inscription. As it stands today, this object is rather complex; it is in part an intimate artifact from a great ruler but also a nineteenth-century cultural appropriation, which has converted the artifact into a trophy. This adaptation of the object by an English (or Canadian) owner suggests both a reverence for Tipu Sultan as a renowned sovereign, as well as a proud demonstration of triumph and ownership.

For more information about the original context and significance of these objects, check out the publications related to this collection, including the exhibition catalogue Treasures from India: Jewels from the Al-Thani Collection and Beyond Extravagance: Gems and Jewels of Royal India.

Courtney Stewart

Courtney A. Stewart is the senior research assistant in the Department of Islamic Art.